毎日新聞社より記事掲載の許諾を得ております。

Descendants of 1860 samurai delegation to US donate English panel for Tokyo monument

TOKYO — A group of descendants of 77 samurai who joined the first Japanese diplomatic delegation to the United States in 1860 has donated to the Japanese capital a panel bearing the English translation of a monument commemorating the historic mission.

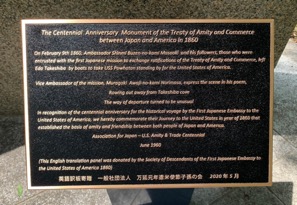

The newly set up bronze panel stands in front of a decades-old, Japanese-inscribed monument at Shiba Park in Tokyo’s Minato Ward, which was erected in 1960 to mark the centennial of the so-called Japanese embassy’s journey to America. The stone monument introduces the delegation, sent by the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1868), as being entrusted with the mission to exchange instruments of ratification of the Japan-U.S. Treaty of Amity and Commerce, as it made a voyage across the Pacific aboard the USS Powhatan.

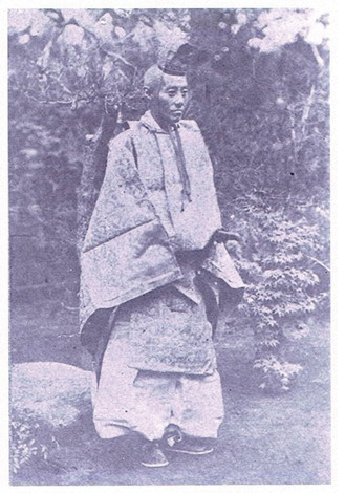

Once setting foot on U.S. soil, the Japanese embassy, as Americans called the delegation, was received with gun salutes, parades and banquets and had an audience with then U.S. President James Buchannan. They visited various destinations spanning from San Francisco, Washington by way of Panama, Baltimore, Philadelphia to New York. And even though their aim was to primarily promote trade and amity between the two nations, the delegates also brought home modern technologies and culture while leaving lasting impressions on Americans, just before the two countries were embroiled in domestic turmoil from the U.S. civil war in 1861-1865 and Japan’s Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Although the descendants’ group was planning to hold a ceremony to unveil the English panel this spring, it was canceled due to the spread of the novel coronavirus. When the panel was finally donated to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government on May 13, 2020, the capital was still under a state of emergency, and just three people — the group’s representatives and a metropolitan official — were present before the monument, located near the famous Tokyo Tower and Zojoji, the family temple of the Tokugawa family.

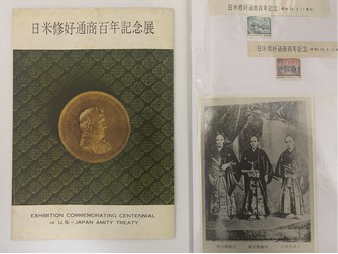

That was a modest sight compared to 60 years ago, the centennial of the 1860 mission, when the monument was unveiled at a ceremony with the attendance of scores of people including then U.S. Ambassador to Japan Douglas MacArthur II, nephew of Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Douglas MacArthur, as well as the then Tokyo governor, descendants of the samurai diplomats and others concerned. The 1960 event made headlines in newspapers and on TV at the time. Besides the ceremony, that year also saw a stream of events in commemoration of the centennial, including a large-scale exhibition at Isetan and Hankyu department stores showcasing numerous items including those kept by descendants’ families, as well as a banquet, a music concert, sailing ship cruises, and even a TV drama themed on the delegation aired by public broadcaster NHK.

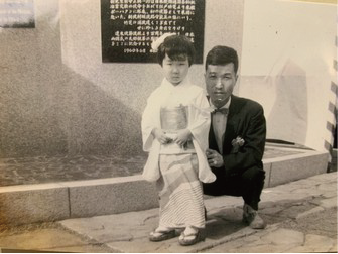

Mariko Miyahara, 65, great-great-granddaughter of Muragaki Awaji-no-kami Norimasa (1813-1880), who served as vice ambassador of the 1860 samurai delegation, recalls pulling the rope to open a white curtain covering the monument during the unveiling ceremony at Shiba Park as a then 5-year-old girl clad in kimono, on June 27, 1960. She was among the participants of the ceremony along with her father Masazumi Muragaki, Norimasa’s great-grandson, now aged 97.

“My father was invited to the ceremony on behalf of the Muragaki family, and was asked if there was some lady who could unveil the curtain. My father replied he had a 5-year-old daughter, and that’s how I got to take up that role all of a sudden,” recounts Miyahara. “Because I didn’t have a kimono, my relative lent me one and my great-aunt living next door put it on me nicely.

“I remember Ambassador MacArthur calling out my name (at the ceremony), ‘Mariko-sa—n,’ and he shook hands with me. His hand was big and hairy, which was very impressive,” recalls Miyahara.

As a young girl, she says she didn’t know anything about America, but speculates that because Japanese society at the time was undergoing turmoil over revision to the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, many of these events were held to highlight Japan-U.S. friendship in part to quell that unrest. She says that the address given by Ambassador MacArthur at the unveiling ceremony also provides a glimpse into this aim. At the time, the planned visit to Japan by then U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower was canceled, she noted.

Now a director of the Society of Descendants of the First Japanese Embassy to the United States America 1860 Inc., Miyahara has dedicated herself to informing the delegation’s historic role in Japan’s modern diplomacy since the group’s establishment in 2010.

The group’s members have so far toured Washington, Hawaii and other locations to follow their ancestors’ footsteps both in Japan and abroad, inspecting a trove of documents and artifacts related to the 1860 mission at the National Archives and Records, the Smithsonian Institute and elsewhere. They also set up a monument at Washington’s Navy Yard where their forebears disembarked, and even stayed at the Willard Hotel in the U.S. capital where their ancestors checked in more than a century ago.

Members of the group also met descendants of Americans who hosted and assisted the Japanese samurai envoys during their 19th century journey. There are currently 63 descendants registered with the group, two of them living in the U.S.

The group decided to present the English panel — measuring 30 centimeters by 40 cm with a height of 60 cm — to the Japanese capital this year on the occasion of the 160th anniversary of the dispatch of the 1860 mission and the group’s 10th anniversary, and had hoped that the panel would also be of help for foreign tourists visiting Japan, including those who would have been in the capital had the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games been held this year.

“In the summer of 2018, I realized that many of the explanatory panels set up recently at historic sites had English and sometimes Chinese translations,” says Miyahara. “I wondered if they were developed ahead of the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games, and thought that the monument (for the 1860 delegation) at Shiba Park could also have an English panel set up by the board of education or other authorities.”

Two years later, the panel was finally set up along with English inscriptions translated by Takashi Muragaki, the great-great-grandson of Muragaki Awaji-no-kami Norimasa and honorary chairman of the descendants’ group, and supervised by a linguist. On the panel is a poem written by vice ambassador Norimasa when the delegation took boats from Tokyo’s Takeshiba pier to take the USS Powhatan for the 1860 trans-Pacific voyage: “Rowing out away from Takeshiba cove / The way of departure turned to be unusual.”

“Next year, if the coronavirus crisis is over, we are planning to hold a gathering to unveil the English panel in May, along with a cruise party and other events,” said Miyahara. “I hope many of those visiting Japan from abroad to attend the Tokyo Games next year would come to know the achievements left by the 1860 delegation, which ushered in Japan’s modern internationalization lasting to date.”

(By Tetsuko Yoshida, staff writer, The Mainichi)